Lindsay Perth is a photographer with many talents. Besides Lindsay Perth’s Edinburg based commercial, street, and documentary work, Lindsay also once studied print-making, has made short films and has created several art installations across the UK. Lindsay has that multi-disciplined curious flair you only see in the truly ambitious. And Lindsay Perth’s photography feeds on those many faced passions. I was immediately drawn to this experimental and bold work, especially the photo-montages from A Sense of Someplace.

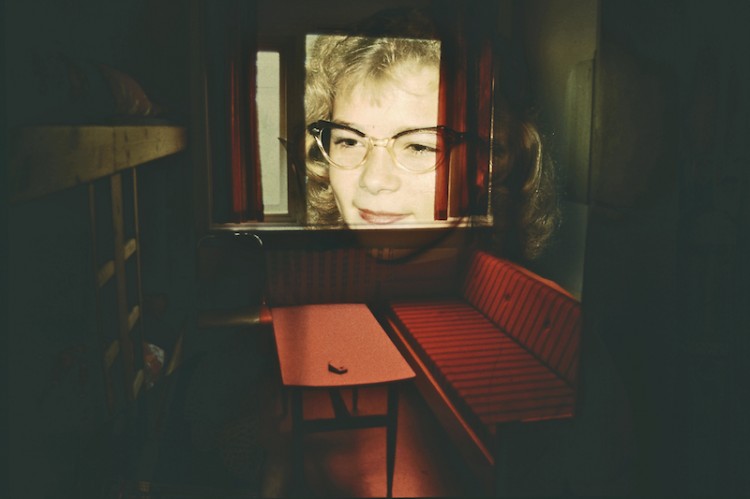

Made through a collaboration with the patients of the Forth Valley Royal Hospital in Scotland, these montages put together separate 35mm slide format images into one single mount and view. Alone, the individual 35mm slides are ordinary. Yet juxtaposed together, something happens. They morph into a surreal — at times puzzling — symphony of metaphor and emotion. They remind me of waking up, of seeing the world slip in and out of dream. They capture what I visualize an epiphany would look like. And that’s pretty darn impressive, to say the least.

In this interview, Lindsay Perth talks about Lindsay Perth’s art and how Lindsay got into photography, explains Lindsay Perth’s projects and their processes, and reveals the artistic influences of Lindsay.

I like the experimental nature of your photography. How did you get your start? How would you describe your work?

I would consider myself an artist before I’m a photographer. I choose to work across several disciplines although more often than not my work is lens based, photography or film, but I would never restrict myself to these. I started using photography while at art school doing a Printmaking degree. I was massively into photographic screen-printing. I started taking photographs to use in my screen-printing, manipulating images directly on the screen and I was using found photos as well. Now that I think of it, 20 years later, that was probably the period I fell in love with photography but I didn’t quite have the confidence to use it the way I do today. I went towards moving image for many years and returned to photography about ten years ago. It’s only in recent 6 or 7 years I find I have a clarity and focus about my work and where I’m going with it. I’m preoccupied with between states, flux and the tension of doubt and ambiguity. I have a fascination with states of change and the wilderness that exists when something you think you know isn’t what you thought it was.

You work within many disciplines, utilizing film, photography, and performative art. I especially like A Sense of Someplace. Could you explain what inspired you to start this project?

A Sense of Someplace came from my 2 year arts residency with Forth Valley Royal Hospital. My time was divided 50/50 by collaborative work and my own arts practice. For the collaborative aspect I chose to work with a group of people who were users of the mental health services. Initially, I proposed to work with narrative photography by setting up scenes that had an ambiguous tension that dealt with personal experiences of mental health. After many months of looking at photography such as narrative, documentary, street and discussing what photography is, I realized I was putting people in a situation they weren’t ready to take on. My end goal was for the collaborators to be the subjects in their photo series but this, understandably, was turning out to be a creative barrier for many. I needed to find a way for people to feel free to create powerful photographic images without them feeling exposed. So I took a step back for a few weeks, did a lot of thinking and I decided to buy a heap of family archives in 35mm slide format, mostly from eBay and car boot sales. At the time I had thought about projection onto surfaces but once I had the film slides in my hand I became mesmerized by the physicality of the film, the personal histories and how our pasts are represented through the lexicon of the family snap. These images are full of odd out of context moments and intimate scenes of family life as seen by the photographer. I began to take the slide mounts apart and experiment with an old slide projector. Eventually I began to put 2 slides together and put them in a single slide mount and view. The results were fascinating, so full of story and juxtaposition. The familiar visual language of the family snap became enigmatic. The resulting montages fluctuate between two times and place but as one they create a narrative that’s very cinematic and become compelling allegorical images. I asked the group if they wanted to work this way, using anonymous family archives as our source material and they did. We spent months trawling through these hundreds and hundreds of slides looking for slide pairs that ‘worked’. We created about 65 images, 25 of these went into the publication. My hope is to have the images printed large-scale with the intention of touring them. I’m seeking funding to take the images to a wider audience.

This project features much collaboration between you and mental health administrators. What was that process like? How did you keep it all organized?

It was a fascinating experience working with the NHS as an artist in residence. I learned a lot about the complexities of large-scale organisations, the desire for people who work in them to be challenged and included. I also learned how to be more flexible and patient with regard to my own objectives. And I grew some thicker skin, which is always a good thing when you’re putting your work out there all the time!

The third image of A Sense of Someplace featured on your website is my favorite. There’s something sinister about it – at least to me. Her expression and the slick red leading to the window seem like a view into someone’s fragile interiority. What was your process to juxtaposing images? Did you go off intuition?

I mentioned before about the physical process of taking slides apart, pairing them and remounting as one slide to create a photomontage. But this really took quite a long time as the two slides needed to work and have a sort of transformative result. Sometimes we’d sit in silence for hours taking them apart, putting two together and viewing it in the projector… it was quite a laborious process. We had spent many months looking at photography, the narrative of a photograph and discussing the many roles photography holds for us and I think this gave a confidence to the collaborators to trust their intuition when something worked. That was certainly a successful part of the project, collaborators developing their creativity as image makers, working intuitively with confidence. It was quite fascinating when someone would put a montage into the slide projector and we’d all look up to see it and often people would gasp. When projected these images are much bigger that what we see in the newspaper, a book or a monitor. And in a dark room they really were quite astounding when we first viewed them. So when a montage ‘worked’ we discussed what we saw and very often the photomontages have a kind of, and I think your words say it better than mine, a fragile interiority and sometimes yes, they feel quite malicious. And many have a beautiful sadness to them. What I delight in most in the photomontages is that they provoke a feeling that I would find difficult to put into words. And for me that really underlines their powerful narratives.

Does working within different disciplines allow you to see certain expressive harmonies that otherwise wouldn’t be considered if working within only one form? How do the other disciplines inform your photography?

You know, that’s a good question. I think by not putting boundaries on myself to show work in traditional forms and striving to consider who and how people experience my work is perhaps more a driving force than any discipline. The thing is, and I know this is rather utopian, I want my work to be seen outside the artworld as well as inside and that doesn’t always work very well, especially with collaborative art. The last work I made for my NHS arts residency was a film, entitled ‘One Hundred Blinks’, that I projected large scale on the outside of the Hospital. I’ve never done a site-specific installation of that scale and I sense it won’t be the last. It was quite a different experience and impact to have an artwork 40ft x 60ft high and viewed on a public building. The film, a series of portraits shot in extreme slow motion, seem like still images until the wind moves some hair very slowly or there is slight movement in the background. Certainly working with moving image informs my photography and vice versa and I would say performance and installation do too. Site specific and performative work, by its very nature, demands more consideration when working with other disciplines like photography or video so a lot of informing across disciplines happens.

A lot of your photography works with stationary, inanimate objects: windows, murals, chairs. You seem drawn to sets of three. When out shooting, what helps you find interesting compositions? Do you have any artistic guidelines?

For me, spaces that have no actual human presence have more room for the viewer to create the narrative. They are static and have a silence I find very seductive. Often there are clues about who was there, when and possibly even what happened or could happen and that ambiguity is what I like to record. A deserted dining room table after a meal speaks volumes. The funny thing is, discussing this here, my work is going through some changes and I’m moving towards portraiture. I think I’m looking for a different kind of soulfulness, that’s more tangible through portraiture? I’ve made that question. I’ll get back to you when I know more. But still, I’m always looking for empty spaces with evidence or clues that can tell many different stories at once. When I’m out shooting, I tend to hang around in one place and watch people as they go about their day, wait for buses, etc. and find juxtaposition or objects that give clues about human presence or narrative. I generally don’t crop in post-production. I do as little as possible in post and create the composition at the time. Many years ago, a photographer whose work I respected, told me to frame and compose the photo I want at the time, don’t rely on post-production. I still work that way.

Your Disruption series is great. My favorite is the first one featured your website. It is simple yet provocative. Could you explain how this image was made from start to finish?

The Disruption series came from my ongoing preoccupation with interruption and dramatic ambiguity. I wanted to really push this idea and create a precarious thin line of uncertainty – what has just happened? What is about to happen? I once come across a car accident and it was like a moment frozen in time yet there was so much intense action going on as medics arrived and dealt with the injured. It’s the tension of a broken quiet or the anxiety of disparity that I want to create. The images in the series are reconstructions of iconic photographs of violent events in history, and the characters in the original images are male. The original images are fascinating, they have become so famous that the photograph’s drama, body language and composition has superseded the photograph’s role as witness to an actual event to represent popular understanding an era or happening. So what happens when you use the familiar nuances of these photographs and change them to create other narratives? They are peculiarly familiar yet any narrative is quite different to its original. I wanted the series to be provocative by disturbing established stereotypes, so I changed all the characters to women. I want the images to disrupt our collective memory of these iconic photographs of history. I used social networks, made posters and spread the word that I needed women to create large scenes of people to photograph and I sent them all dates and locations for the shoot and the image I would be recreating. From there I just waited to see who turned up and sometimes I called upon passers-by to make more numbers. Then I set up my lights, I generally had two assistants and choreographed the women. I didn’t ask for any permission in the locations, some I probably should have but I was on a timescale and needed to get the work done for an exhibition. I was also pregnant and didn’t have much energy for carting lots of kit around and climbing ladders!

What advice could you give to other photographers looking to experiment with the scope of their photography? Any artists you find especially motivating?

Never underestimate the importance of playing with ideas and always make time for it. It is an imperative part of learning more about yourself as a creative individual. And don’t feel you have to use the tools they way they were intended. Experiment, take risks, make mistakes. It’s the best way to develop your own creativity. Oh and don’t try to do everything on your own. I made that mistake for many years. Collaborate, do favours for each other, work on each other’s shoots, give/get feedback. And print your work. Don’t let it all stay on the screen. Astrid Kruse Jensen, Lee Friedlander, Ed Ruscha, Martina Geccelli, Hiroshi Watanabe, Nina Berman, Tabitha Soren, Aernout Mik to name but a few.

Be sure to check out all the work of Lindsay over at: