Having to write an introduction to conceptual landscape photographer Jeremy Dyer’s work proved incredibly difficult, so instead of my usual grandstanding I’ll tell you what I was listening to while finishing this interview: It was Portishead’s Third album. Try it. Put on “We Carry On” from that album then browse through the images of Jeremy Dyer, let the bass and dark synths tremble alongside the photographs of Jeremy Dyer, let “The taste of life . . . ” echo beside the stark of Jeremy Dyer composites. If you’re anything like me, you’ll love how they complement each other.

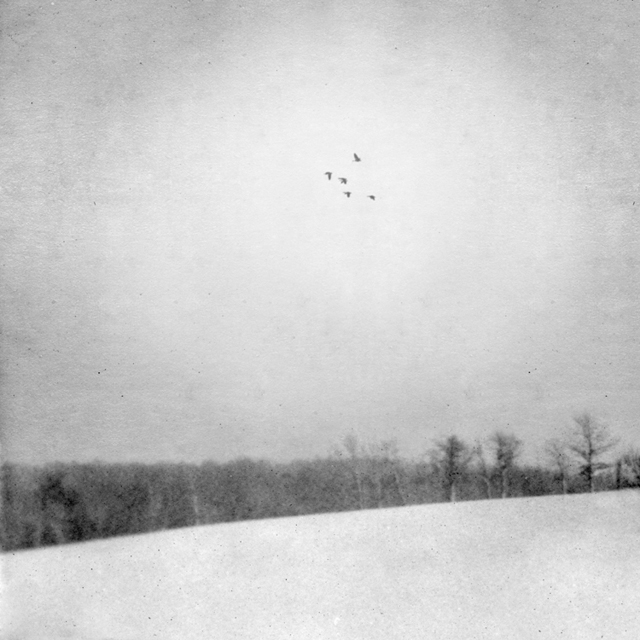

Why? Because the images of Jeremy Dyer are about loss. They are not complete. The images of Jeremy Dyer are composites, and in being stitched together, “painted” as a whole, they are about stories, feelings, and memories that no longer exist. In short, they are fictional spaces created from the orphaned photos of what Jeremy Dyer has found around him. And although these images are some the bleakest I’ve ever seen, they were intentionally created to reawaken moments of lived experience — moments which perhaps could’ve been lost forever. So like the shivers that join us when we step out into the cold, these images are about preserving whatever warmth is left in these found moments of time.

In this interview, Jeremy Dyer talks about his unique approach to landscape photography, explains the details of how Jeremy Dyer arrived at compositing found imagery and reveals why you shouldn’t overthink your work.

Your work is wonderfully intense. How did you get your start?

Thank you! I first started taking photographs at local punk and hardcore shows. The scene that I was a part of had a very DIY ethic—if you wanted to play in a band, start a band. If you wanted to see a show, put one on in your parents’ basement. If you wanted to put out a record, press it yourself. I wasn’t in a band, and I didn’t write a zine or put out records, but there was this vibrant intensity that I wanted to participate in beyond just being in the audience, and documenting the scene was a way for me to do it. It gave me a strong sense of my own agency as a maker, which has stayed with me. Even though it may not be very apparent, I’m still strongly influenced by music subculture with the images that I make now.

How would you describe your work?

I’m not really sure how to describe my work. I’m always a bit puzzled as to how to respond when I’m asked. I think of myself as a photographer, even though what I do is miles away from straight photography. A friend described what I do as “painting with photographs.” I guess if pushed, I would say that I make landscape photographs about myth, memory and loss that are often very grimy. My favorite thing that I’ve ever heard said about my work is that it’s “not nice for grandmas.” I’m not totally sure what that means, but I’ll take it.

Haemal is a brooding set of landscapes and portraits. I really like it. Could you explain your aim with this project? What made you want to capture the world in this way?

The images that I create are fictional spaces–they depict locations constructed from portions of my photographs and elements taken from found snapshots and family photos, and explore the space where memory, history, culture, and myth overlap in the landscape-as-image. With Haemál, I wanted investigate how memory, history and the impulse to mythologize intersect with our relationship to land and location. Working with only photographic elements–trace records of things that were at one time actually present in front of the camera–has a deeper resonance with history and memory than I could achieve with painting or drawing. Visually and thematically, Haemál is influenced by Scandinavian myth and folklore, the aesthetics of underground punk and metal culture, the USGS Photographic Library, and the tradition of the sublime.

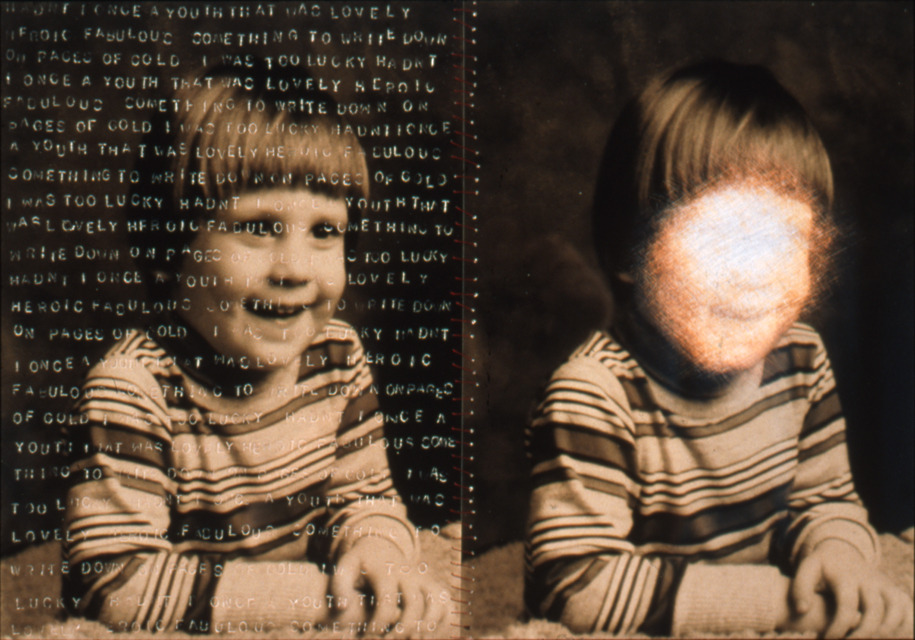

I’m not really sure where the initial motivation for making these images came from. I think that there is something innate in photography that touches on loss and change. Someone (was it Barthes? I can’t remember) said that all photographs of children are essentially images of dead children, in that they are the frozen moments of time and always exist in the past and never the present. I’ve always been attracted to old photographs but didn’t think about using them as material until I was an undergraduate, when a friend’s elderly neighbor passed away, and she found her childhood photo album sitting on top of a pile of garbage waiting to be hauled away. She took it and gave it to me. There was something so incredibly tragic about this photo album to me, with its meticulous captions and precise layout. The album was a physical artifact of this woman’s memory, bits of her lived experience that she kept returning to, and all of its relevance and meaning was lost with her passing. I worked with these orphaned photos, trying to extract whatever essential meaning I thought I could find in them.

I came back to working with found photographs for this series. I love incorporating traces of my lived experience (via my own photographs) with the fragments of other lives. The way that these images come together mirrors the way that we construct memory, collapsing bits and pieces from different times and places into one cohesive image. The analogy that I like to give when I’m giving a talk is that the process for me is like an early memory of one particular morning, eating cereal at the kitchen table in my grandparents’ house, which in actuality is probably the sum total of my recollection of all the times that I sat at that table eating cereal. To me, this construction of memory is a lot like the construction of myth, with all of these disparate elements coming together into an essentialized whole, something that exists nowhere but comes out of something lived.

Which equipment did you use for this set? Any special techniques you hadn’t used before?

I use anything and everything to make these images. I shoot mostly digitally these days, but I still occasionally shoot film (35mm and medium format, and everything from toy cameras to a Hasselblad) and I have an archive of old negatives that I’ll draw from. When working with the found elements, I mostly rely on a heavy-duty scanner, but will occasionally re-photograph them. My whole process of working like this was new with this series — they grew together. Much of my prior work involved hand manipulation and alteration of the final print. There was something a little too detached about traditional photography for me. Unlike painting or drawing, the whole process is mediated through other technology, and I wanted to add something back that involved direct manipulation with my hands as well as room for chance after the shutter clicked. Of course, as soon as I moved to New York I no longer had access to affordable studio space and had to find a new way to work. Using the computer wasn’t quite as satisfying as working with my hands, but it did open up a lot of new possibilities.

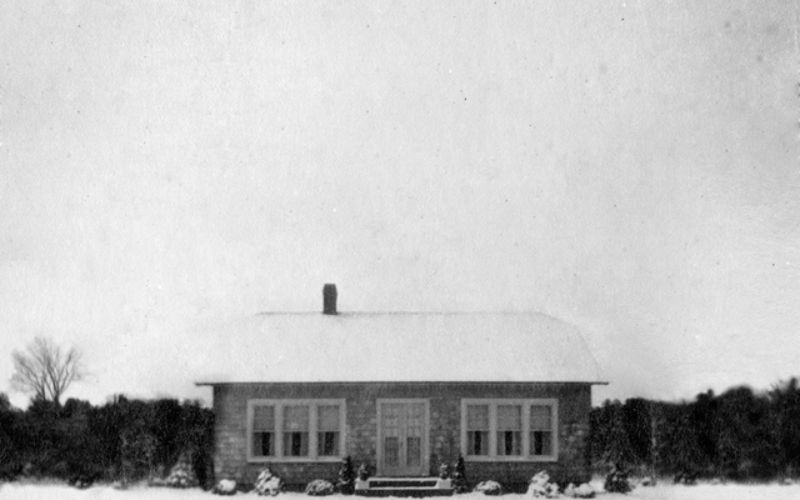

The real genesis for my working method came with the image Heimat (above). Since my foundation is in drawing, I have almost always started with sketches and drawings before I ever push the shutter. I had an image in mind that I had been searching for in the world but couldn’t ever quite find anything that fit. I had dabbled a little in using Photoshop for other images, but it never really went anywhere, until I decided to try “making” the image myself. I collected the bits and pieces of the image by shooting elements that I liked and scanning bits that fit from found images and digitally stitching the whole thing together. The end result was built from something like 25 or so different photographs. It was a lot of trouble for a relatively straightforward image of a house in the snow, but it opened up a whole world of possibility for me. I should note that everything in the images is photographic in source. I don’t use filters or texture brushes and I don’t take images from the Internet. It’s important to me that everything that goes into the image is “real” and represents the trace of something that was once physically in front of the camera. If I didn’t shoot it myself, it needs to come from a physical print or negative.

I love working with pieces from found images (most frequently either taken from my family’s albums or from flea market finds). I love that they are physical objects, subject to change and decay and carrying traces of their history (smudges from a finger, creases from being carried in a wallet, etc). I try to reintroduce some of this sense of the physical “mortality” of the photograph into my images through the texture. I want the final image to be as seamless as possible and I want the “digitalness” of the process to be as far removed as possible. It’s crucial conceptually to me that the images are composites, but I don’t want that to be immediately apparent to the viewer.

The first image (above) in that set is one of my favorites. It is of a black sun over a lonesome field. Why do you think you’re drawn to photographing these unconventional landscape images? How did you capture that black sun exactly?

You know, I never really had much interest in landscape imagery. I grew up in Southern Arizona and I was spoiled by expansive vistas and incredible landscape photography at every turn. Maybe because I was experiencing it as part of my daily life, it didn’t hold a lot of resonance or interest for me as a source for my work. I had dabbled a little with landscape imagery as an undergraduate (I collaborated on a semi-documentary project with Luke Stettner on the effects of overdevelopment in the desert), but it wasn’t until I moved to New York that I started actively making landscapes. I didn’t recognize it for what it was at first, but more and more landscape imagery and expansive vistas started creeping in to my work. I think that maybe on some level I was trying to make something to replace the boxed in, broken up and claustrophobic urban space that I was now surrounded with. Of course, the end result tends to not be very pastoral or bucolic. There is something in the Romantic Sublime that resonates with me, that idea of reacting to the natural world with a mixture of awe and terror, with the landscape being a site for indifferent and dangerous natural forces beyond our scope of understanding. It’s a reaction that Edmund Burke wrote about and that you see in the paintings of Friedrich and Turner. It’s also an idea that’s worth revisiting—we’re in the middle of a period of catastrophic environmental change and we don’t know where it’ll end up.

As photographers, it’s tempting (and rightly so!) to want to make majestic and beautiful images of the landscape and other wild spaces. It’s a part of our vocabulary. I’m inspired by the work of photographers who see the landscape as a possibility for other kinds of conversations, like Mark Klett’s approach to the landscape as a way of seeing time and history, or the Parke Harrisons’ use of natural imagery to talk about environmental issues. I’ve watched the natural environment that I grew up in bulldozed, burnt, built up, or otherwise destroyed in the name of growth, only to be abandoned and left half-developed as the market went belly up. I think that on some level that experience comes through in the barren and razed spaces that I depict. As to the black sun, it was made by way of some low-tech, old-fashioned photographic trickery. For me, I’m interested in the black sun both for it’s apocalyptic overtones and it’s alchemical significance for a state of change.

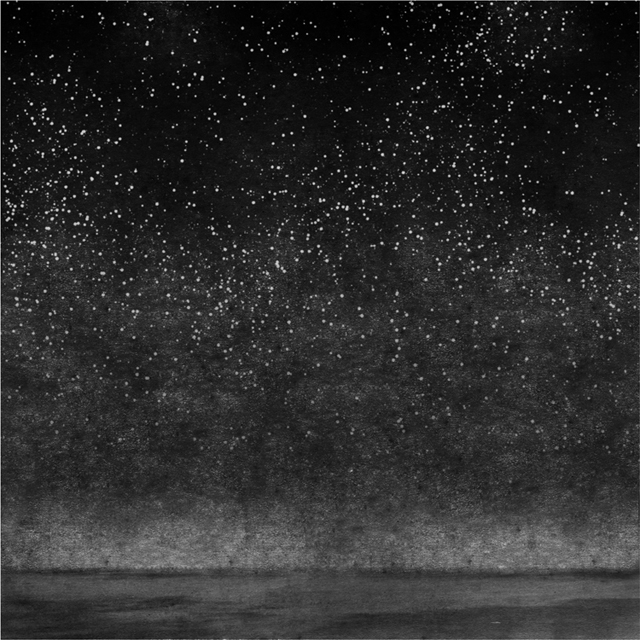

The third image is another favorite. Although it is bleak, I think it’s the most hopeful of the entire set. What was your photographic process with this image? How did you achieve its murky texture?

It was much the same as the rest of the series, built up from many pieces and layers. I let the paper texture with its dirt and grime and physical deterioration be more apparent and blend with the star field. Visually, I was trying to recreate the experience of the desert night sky in winter, the cold stars visible against the last remnants of light from the sunset or the reflected glow of city lights in the smog of the nearest town.

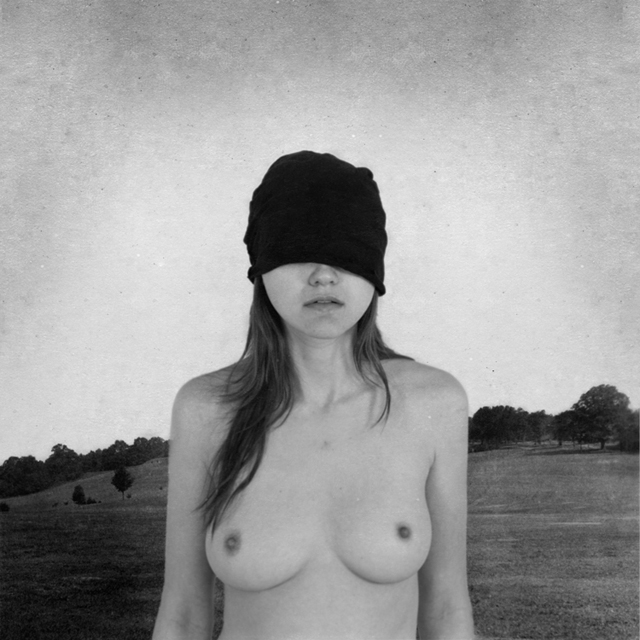

What is your approach to portraits? They all seem to have a narrative aim.

I think the portraits are similar to the landscapes in that, where the landscapes are not images of specific places, the portraits are not meant to be about specific individuals. It’s something that I like in medieval painting (and especially altarpieces), where it’s more about the idea or the essence of the thing rather than a singular identity. Funnily enough, I originally envisioned this series being made up almost entirely of portraits and narrative moments, with the landscapes being constructed as a sort of stage for the “action”, but the landscapes became more and more important to me and have almost completely edged out the figural.

If what we shoot shows a little about how we think, what do your stark images say about you?

Eep, I shudder to think what my images might say about me. My process describes me to a “t” in that I am taking something that should be relatively straightforward and making it into something waaaay more complicated and time-consuming than it has to be. Somehow it’s more satisfying to me that way. But seriously, I think these images are my way of working through my own history and memory, and are maybe a way of coming to terms with mortality. To my surprise, I’ve discovered that working on this series has also been a way for me to sort out and make peace with the changing natural world that we’re living in. I recently discovered a British arts journal called “Dark Mountain” and in their manifesto, they state that their mission, rather than to despair in the face of environmental destruction and cultural loss, is to make new myths and songs for the changing world. I like that.

What would you consider the best advice you ever received about making photographs?

I’ve been blessed with many amazing friends and mentors, so it’s difficult to think of one key piece of advice. I do often hear the voice of one of my earliest teachers, Ken Shorr, saying not to worry about the what or the why or the how, to just make the work and trust that the rest will become apparent on its own. It’s stuck with me whenever I’ve gotten blocked or started to overthink my process and my work. Just make, and trust that everything else will sort itself out in the end.

Be sure to check out all the work of Jeremy Dyer on his website and blog!