She was short, not much taller than five feet, strong-willed, and always ready to fight. She had brown eyes, Mexican through and through, yet she had red hair and the whitest of white skin — vitiligo — though never failed to laugh or find a reason to cry. But that’s only how I remember her. She could’ve been other things. What’s true is that my grandmother’s life has become a way for me to navigate my own. My whole story is about hers.

And this gets to the heart of it. No matter what I think, my grandmother wasn’t unique. She was, of course, rare — tough, rugged, and wild. I still remember her ability to cuss like the meanest cut-throat you’ve ever met and still brag that it was her who taught me how to throw a punch. But she also felt deeply, all the time. She was protective and caring. My story, however, probably resembles yours. I’m sure we’ve all met a woman like my grandmother.

I know she would’ve fit in with the women photographed and championed by photojournalist Shaena Mallett. She probably would’ve maintained the energy, even at her oldest, to run alongside them. And she would’ve appreciated a photographer doing the same. Being the greatest storyteller I’ve ever known, my grandmother would’ve seen the necessity of the work of Mallet and been grateful for stories like hers being told by a photographer like Mallett.

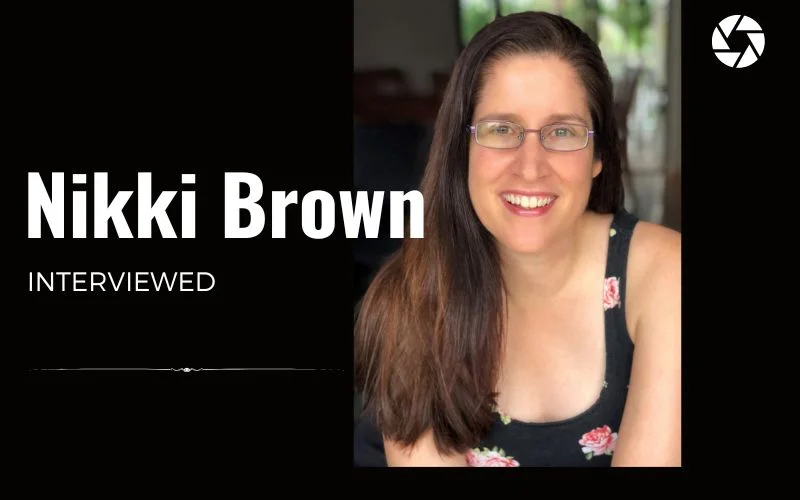

Oh, one more thing about Mallett: You know you’ve met a wise person when you’ve met a truth never before known to you. And I met more than once while reading the answers given by Shaena Mallett to my questions. In the words of Mallett and her photography, I encountered a photographer willing to express vulnerability. As Mallett explains it, “Life is heartbreakingly beautiful. At my core is hope, always. I want to make pictures that are like a love letter to life: honest, tender and above all, grateful.”

In this interview, Mallett talks about her rural upbringing and her family, speaks about her start with photography, and gives honest advice about making heartfelt imagery.

I really like the vulnerable romanticism of your images. How did you get your start? How would you describe your work?

I’m the youngest in a family of amazingly creative and hardworking folks, and they’ve inspired me to create as long as I can remember. In college, I studied photojournalism and anthropology, and assisted in a therapeutic photography program. Over the years, photography has been a steady companion. I’ve always found words to be really difficult and I find such comfort in being able to visually interact with the world and show rather than tell. I think vulnerable and romantic are both great words to describe how I function in general. When I work with a camera my personal goal is to stay dreamy but honest, documentary but poetic, and to always try and channel the sense of hope that I carry with me. I don’t know if that comes across in my photographs, but that’s what I work toward in the process.

You work as photojournalist and also as wedding photographer. All your images share an unvarnished rawness. You seem to really enjoy getting to know people through your work. Do you have separate approaches to each genre? How does working in each help you overall?

I do really love getting to know people, and a camera is such a great excuse to be brave and show up in situations I might never be otherwise. I think I do have somewhat different approaches for photographing weddings and personal documentary work, just because the nature of expectations. For weddings, the amount of pressure and energy that is focused on pleasing a client is so demanding, it can be a challenge to maintain a freedom of vision. When I shoot documentary work, especially if it’s just for myself, it’s a lot easier to tap into my creative voice. I’m learning how to be bolder with weddings and it’s feeling good. Weddings are such a brief, intimate look into other people’s lives – emotions, family dynamics, hopes for the future. Sometimes I have these moments where I remember that people’s grandchildren will look at these pictures in 50 years, and it’s an honor to be a part of that. I think the different forms of photography I do all feed one another. Each one keeps me on my toes and presents its own set of creative challenges to rise up to.

You also seem highly attuned to nature. Even in your darkest set, You Were Here, there’s a deep respect for natural wonder. What do you feel in a landscape? What do you usually look for in a landscape photograph?

I was raised rural. Wild spaces are where I find peace and the spiritual force. Everything is connected. Every mountain and animal and plant: we are always shaping and changing and affecting and sustaining one another. It’s so healing for me to sit and listen to a place, to quiet my mind, and to practice seeing things instead of just looking at them. As far as involving a camera, I just let myself wander until I find the intersection of an external landscape and my internal landscape: when they reflect one another. There is this magical moment of recognition and connection. That’s the picture.

For example, You Were Here #21, though gloomy, still conveys calm and perseverance (those telescopes still stand together through it all). How did you find this location? Were you just walking around? Could you explain how this image was made from start to finish?

It was the beginning of January and I had just moved to Vermont: I was feeling lost and was processing a very fresh breakup. It was a painful path from loneliness to solitude. I drove all night to the coast of Maine, hoping to watch the sunrise. Instead, I found the ocean in a raging blizzard. It was beautiful and frightening and incredibly humbling. There were no other people, just the remnants of life dotting the landscape. I found a lot of solace in those things that were still there, standing strong in the battering weather. It was cathartic to be completely hushed by this epic external force. I would drive along the coast so very slowly and stop at whatever beach or outlook I could, jump out of my car and photograph things that caught my eye. I remember it was so cold and windy my camera was having a hard time functioning and my pockets kept filling up with ice.

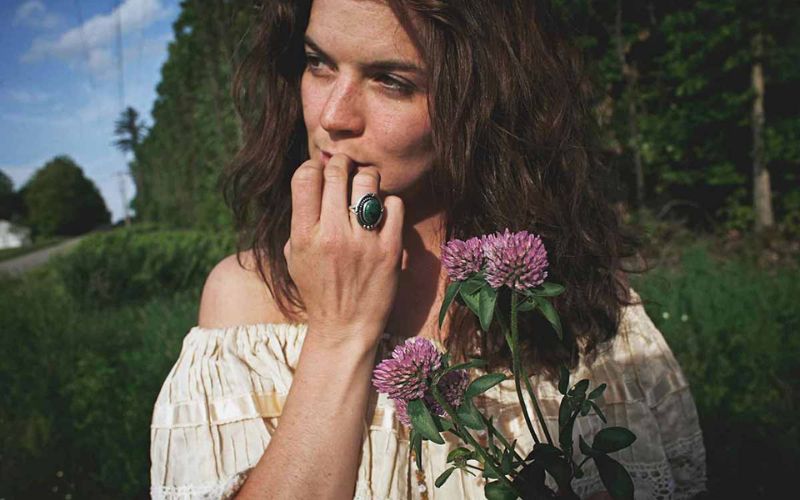

Speaking about this gloom, almost every image you capture seems to have a shadowy undercurrent. Even in your bio’s self-portrait, the black, the reds, and your eyes, all add up to a small sense of sadness. Do you feel this? What’s your usual approach to self-portraits?

I think I just feel. A lot! It’s been a lifelong process of finding a lot of strength and power in sensitivity. Life is heartbreakingly beautiful. At my core is hope, always. I want to make pictures that are like a love letter to life: honest, tender and above all, grateful. So far with self-portraits, they’ve happened in fleeting moments of inspiration without a lot of planning. I see them as a way to check in and write a little letter to my future self about how I’m feeling now. I try to take at least one or two a year. It’s also been a way to explore body image issues and self-criticism, to try to be honest and gentle with myself, to be exposed and bold. I tend to feel inspired to take a self-portrait interacting with wild elements – documenting my own wildish woman nature.

But, overall, your images work toward a 19th century sense of romantic optimism. For instance, I Remember #27 is immensely beautiful. Was this captured with natural lighting? What was it shot with?

Thank you! This photograph was made inside of my grandparents’ home, where I spent much of my childhood. It’s a humble little cabin right on the Allegheny River in Western Pennsylvania. My grandmother infused this rustic little cabin with so many sweet, “lady-like” things – lace, silk flowers, her costume jewelry, her perfume. Whenever I’m there I find myself reflecting on her lessons in womanhood and on my own femininity – this dance between wildness and delicacy. The photograph is a bouquet of lace flowers in her bedroom, and the light is from a tiny window just above the flowers. It was taken on a Canon 5D.

You also shoot portraits. What sort of look are you usually drawn to? What’s approach to direction? You tend to empower the people you photograph.

Portraits are so powerful and vulnerable. I love them and I’ve often felt terrified to take them. It’s a gift, to just stop and share a moment of really seeing someone. So many kinds of faces draw me in. Recently I’ve started shooting medium format film, which has been a great inspiration for more portraits. I’ve been finding myself drawn to faces that are rugged and untamed, like farmers and naturalists and craftspeople. When I approach someone for a portrait I try to keep it simple, to be kind and to be authentic. I try to never direct a person in a portrait to think or feel a certain way. I don’t want to have that kind of influence over them. Rather, I ask the person to have a neutral face, and together we take a deep breath. And then there’s usually some laughing because the whole thing is pleasantly awkward.

Portrait #16 is my favorite. It’s a tender moment to capture. What was your aim with this portrait? Are those her stuffed animals?

For one of my first big photo projects in college I wanted to explore aging and loneliness. I started a photo essay inside a rural nursing home, and immediately formed a friendship with Mary. She was 85 and took me in as a sort of non-biological grandchild. When I finished the project I continued to visit her often and to take her portrait occasionally. She taught me so much about remembering, aging, resilience and simple pleasures. The portrait came after she told me how the stuffed animals were her friends and kept her company. It was a very sweet moment.

Birds and flowers. They’re everywhere in your work. There’s even a woman with a tattoo of both on her back. Because this woman’s face is never shown and she’s repeatedly photographed, she’s awarded a very powerful presence in your portfolio. What do these symbols mean to you? Who is that woman?

It’s true! I love the symbolism of birds and flowers. The connection between people and nature is such a driving force for my curiosity. I often ponder this: In so many people’s lives, there’s a lack of intentionality with a relationship to nature. People feel far away from it. But we are nature. We are made of nature. And though many people live with a deep divide from the wild, they still cling to symbols of nature. We are constantly mimicking, domesticating, reproducing and displaying nature in our everyday lives. And it’s no wonder: the natural world is where we find ourselves.

I find a lot of parallels with the symbols of birds and flowers and the treatment of the Feminine in modern American culture. They are symbols of freedom and strength and healing that are constantly forced into domestication. The woman in these photographs is one of my sisters. I have always thrived on photographing my family. It’s so powerful to photograph someone you share so much history with (and 50% of your DNA!). I see so much of her in me, and me in her, and yet I also see an autonomous person made of her own unique experiences. There is a whole other level of admiration and trust.

You also advocate getting more women voices out there, getting their stories heard. What steps are crucial to that? How might other women get their work noticed and out there?

Humans use stories to teach one another social norms. Women have traditionally told stories to younger women in their communities as they move through their rights of passage and stages of womanhood. In modern American history, this kind of multi-generational community storytelling has been replaced by the practice of male-dominated storytelling being told at women instead of by women. I am such a big fan of collaborative and participatory type projects that include the women in stories as a part of the process. It’s an issue of representation. Women need to work together to help one another represent women’s stories. On a professional level, I think it’s really important for women photographers and storytellers to support one another and have dialogue together about the process. It’s a big task and I’m not exactly sure what the best way forward is, but I think inspired collaboration is a really great start.

Through the honest and humble lens of Shaena Mallett watching the world for what it really is. Shaena Mallett a creator who has carved a niche of her own.