A landscape photograph is made of things that never change. And if this change comes, it does so slightly, perhaps through weathering or decay.

This is because they are photographs of our most basic things: They are the shapes, the colors, and the forms that we’ve seen. They are photographs that make our lands and cityscapes seem permanent and whole, and perhaps we secretly believe that they are.

The truth, however, is that a landscape image is just how Pep Ventosa has assembled them. They are indefinite and made up of smaller and even smaller things.

The images of Pep Ventosa are like those futurist paintings of the early 20th century. Those paintings that had meant to force movement, however restless and chaotic, into the canvas of a still medium.

The work of Pep Ventosa — like those paintings — construct from disassembled parts: taking the shapes, the colors, and the forms of what was remembered. Through their ceaseless energy to be whole, they show how various the parts are to a complete place.

And that is their beauty. Unlike anything I’ve seen before, his images are able to visualize what collective memory wishes to invent.

In this interview, Pep Ventosa talks about how Pep Ventosa got his start making his abstract landscapes, explains his process from start to finish, and reveals what you can do to make your work stand out.

Q.1 Your landscape photography is really unique. How did your start in this genre of photography? How would you describe your work?

Thank you. I started working with images made with multiple photographs back in the early 2000s, while learning the new digital darkroom. In those days, the resolution of digital cameras was very low, 3 or 4 megapixels.

I wanted to make big prints, so in order to get good quality and greater detail I had to increase that poor resolution. I tried shooting a scene in separate parts and then piecing them back together. I was pleased with the results and amazed with the versatility and creativity of that process.

That led to different experiments and in the end my work has grown into an exploration of the photographic image, finding different ways to make photographs with photographs, images not singularly recorded by the camera.

Q.2 For those who don’t know, could you give a general approximation of your process from idea to final image?

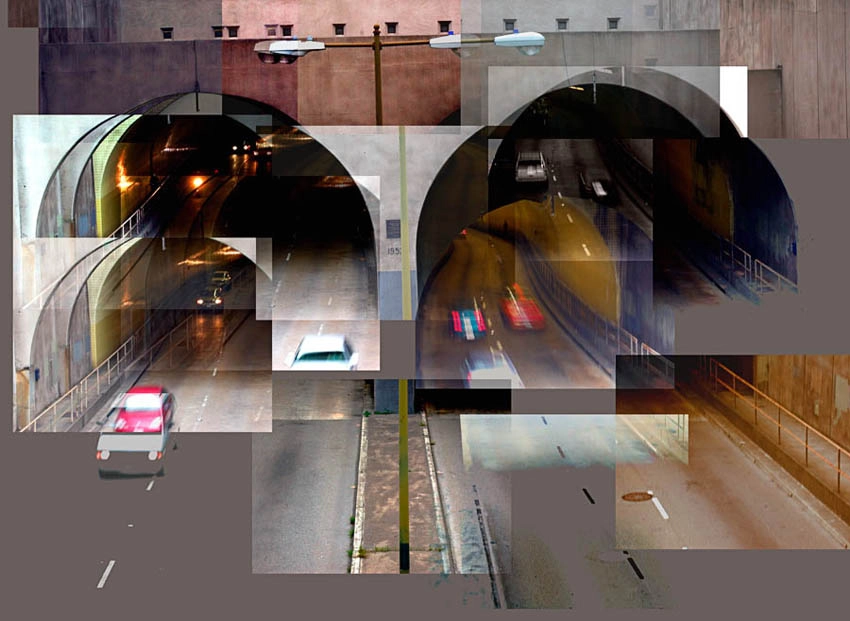

All my images are made using multiple photographs. In the “Reconstructed” series, I first shoot a scene in parts, so each photograph becomes like a puzzle piece.

I then manually reassemble the scene in the digital darkroom, working and fine-tuning each separate piece. I look for balance, rhythm and new relationships between the individual pieces so the final image is a new narrative made of separate sequences.

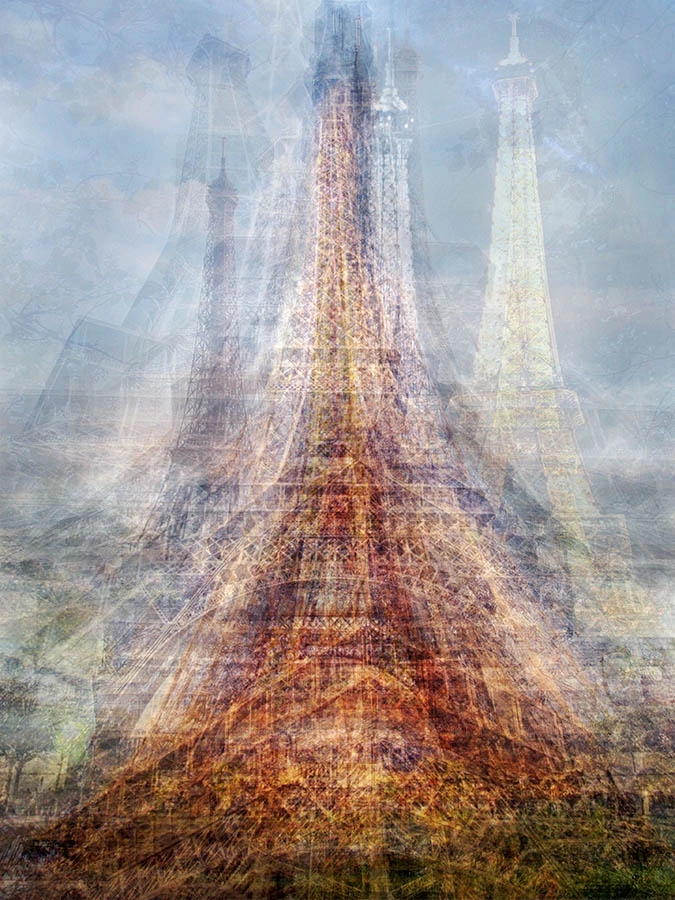

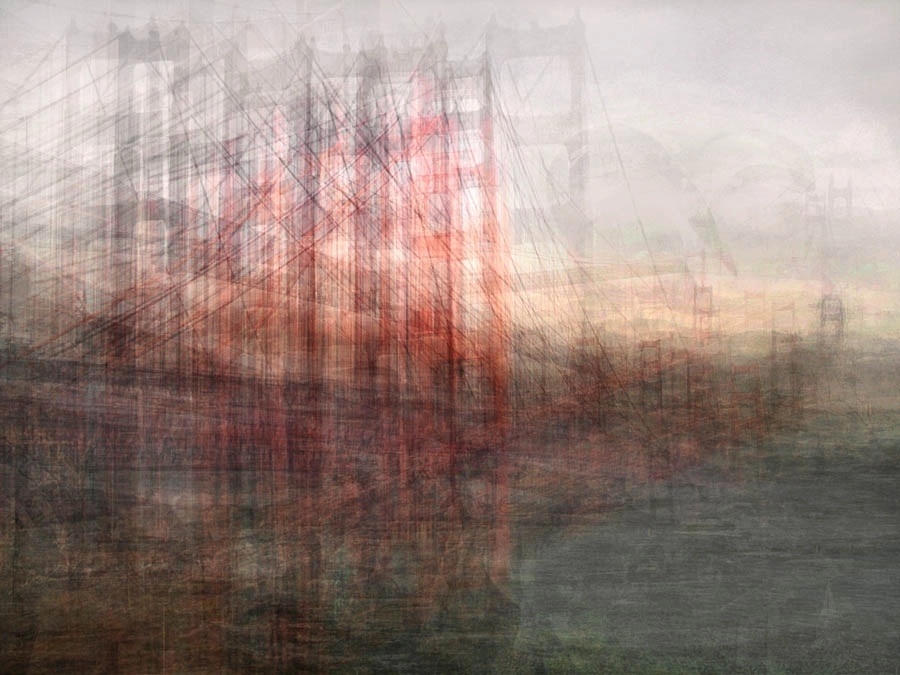

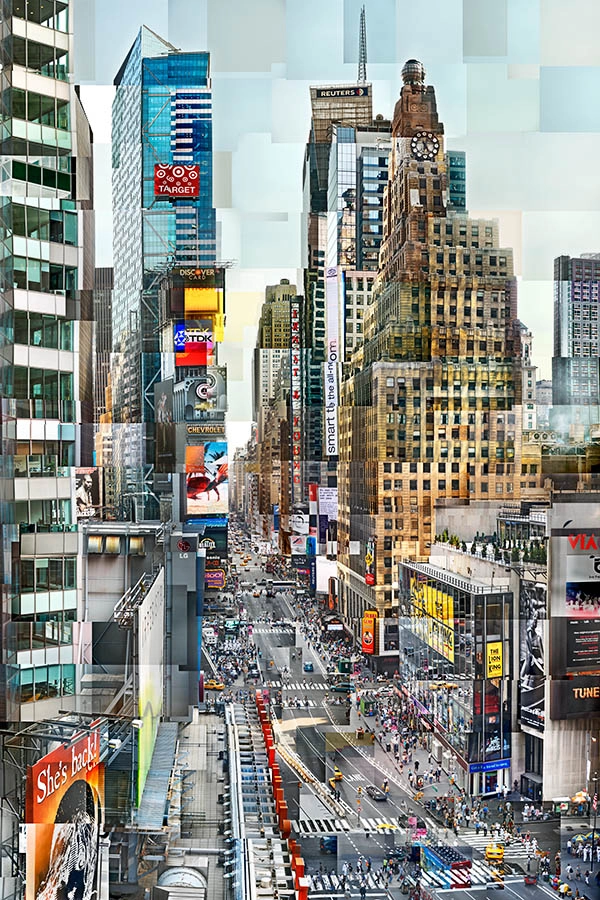

Q.3 The Collective Snapshot project features many abstract re-imaginings of famous, iconic locations. You call them celebrations of our collective memory. Compositionally, what do they say about our tendencies in photographing iconic locations?

Snapshot photography is the most popular form of photography. All the tourists take photographs. Just imagine right now how many people are taking pictures of the Eiffel Tower. As for composition, a common tendency among tourists is to center their subjects, and there are also some consistent points of view.

But what stood out more to me is that, like humans, there are no two photographs exactly alike. The only thing identical is the fascination with the same subject matter.

Q.4 I really like the idea behind this project. You’re building imagined places out of collective perception. Where did you find these snapshots?

The idea of the Collective Snapshot series is to represent a shared vision of a place and celebrate the snapshot as a form of photography. I used snapshots from tourists found on the Internet.

I went through thousands of photos and ultimately selected a few dozen to use as raw material to begin layering together to create a new image; a new representation of the landmark and an homage to the most popular and enduring form of photography.

Q.5 As a celebration of collective image making, the project intentionally avoids critiquing snapshots as memory surrogates. But there’s something weirdly jarring about them. They are both abstract and wild, requiring calm reflection and a quick eye to sort through the collage. Why do you think we are drawn to taking a picture that we’ve seen many times before?

We are social animals. We are embedded in our culture. The snapshot has the power to document our lives; looking at other people’s photos we realize that we share the same emotions, that we document the same experiences: our family events, our vacations.

I guess we take the same pictures to feel part of the same community, but mainly, because we are captivated with the power of photography and its metaphysics: we still believe in what our snapshots show us, and these memory surrogates, as you call them, produce the illusion of a joyful past.

Q.6 After looking through dozens, maybe hundreds, of photographs of one place, did you learn anything that you could share with other landscape photographers about making their work stand out?

We feel attraction to similar things, whether they are places, sunsets or cats. The snapshot may have a specific aesthetic but it has no artistic intention. I think that if you want to stand out you should not take the same picture that has been taken.

Or better said, because virtually and metaphorically all the photographs have been taken already, you can take that same picture but in a different way, in your own way. We all are different, so our pictures are also different, even if they look the same.

As I said, I didn’t see two identical photographs. Find those differences and explore them. To stand out you have to be visible. And to be visible, you have to be singular.

Q.7 All of your work functions through collages. Cayucos from Reconstructed Works, America is one of my favorites. When out photographing landscapes, what goes through your mind? Do you imagine how the landscape will – like in Cayucos – look chopped up into separate blocks?

One thing I love about my smooth workflow is that when I’m shooting a scene, like Cayucos, I can only see the little pieces, not the whole reconstructed scene. From past experience, I have a sense of how it might look, but it’s only a feeling.

To me, that brings back the suspense of the old days of film, the hopes and desires that rose between the shooting and the developing of the film; those expectations and tempo are an important part of my creative process.

Q.8 From your experience making these composites, what advice would you give to other landscape photographers about exploring, or experimenting, with non-standard techniques in their work?

With the new digital evolution, the possibilities of photographic experimentation are endless. So I recommend exploring that potential, with your camera, on the computer, with new materials, new forms.

My intention in photography is to create new visual experiences through pictures made of photographs. Ask yourself: what is it you want from your work, because photography is, possibly, the most flexible of all the mediums.

— Moss Beach, California, October 23, 2013.

Be sure to check out all the work of Pep Ventosa on his website!