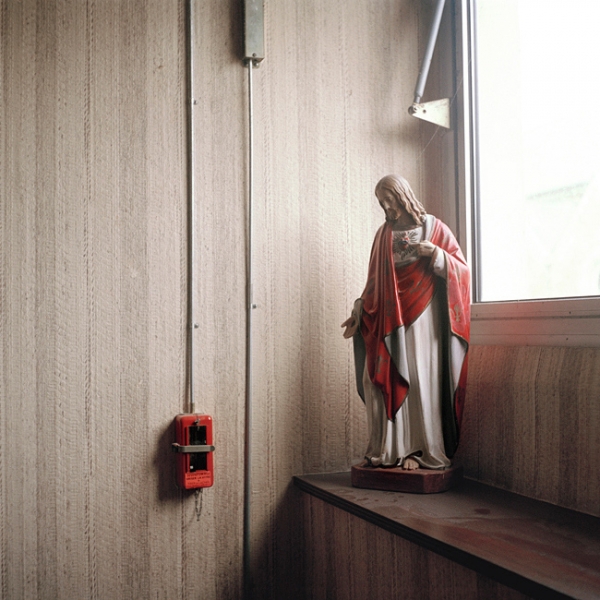

The ward’s entrance is also its exit. Once you enter, the door behind you locks. To look back you’d have to see through windows that are hardly larger than your face. To the residents entering this ward, the door and its windows are the first things they see of their new home. Soon, however, in being a locked exit, the door will become the only thing between them and the memories outside.

Swedish photographer Maja Daniels hadn’t anticipated that this door would become Into Oblivion’s main focus. But after working three years inside a geriatric care center for those who suffer from Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, Daniels began to understand the door’s hold on the residents there. Maja Daniels saw, firsthand, how they interacted with it.

A topic as grim and as real as it can get Daniels has done justice to the subjects Daniels has been loyal to.

Daniels made this project to highlight the institutions and environments that the elderly call home. But the project also investigates what it means to grow old in Western culture, in a culture that privileges the young and the able-bodied. In documenting the hospital, and its patients, as they are, Daniels questions why it is the way it is.

Could we do better, the photographs of Daniels seem to ask? If we’re afraid of dying, of growing old, won’t the institutions protecting those closest to our fears become something we try to avoid? And if what we spend our money on indicates what we value, could Into Oblivion’s subtle sense of dilapidation illuminate what low budgets afford. Old age is part of life as anything else. In the end, all that we value is all that we get.

In this interview, Daniels talks about how Daniels got her start in photography, explains her approach sociologically-minded photography, and reveals heartbreaking stories about the project of Daniels Into Oblivion.

You studied sociology, and eventually transitioned to photography. How did that go? How would you describe your work?

I started out studying print journalism but then quickly transitioned to photography through the school’s darkroom and then ended up studying photography and working as a photography assistant in Paris, and then, finally, I went back to school to study a BA and an MA in Sociology part-time.

I have always been very interested in languages so writing in Swedish for print seemed too narrow. As I spent time in the school’s darkroom, I realized photography’s potential as a global language. Photography also allowed a less “objective” stance in comparison to journalism. Finally, sociology provided a framework that allowed me to better communicate how I want my work to be seen and understood.

Why do you think photography best suits your sociological pursuits? What does photography give your work that the written word doesn’t?

What attracts me to photography is it capacity to tell stories. I like for ‘my stories’ to be rooted in real events, evolve around real people, and ask questions that are relevant to the society that I am part of, but at the same time it is just as important for me to produce a subjective and personal narrative. Since I can only tell one story, I have to make sure it is my own. I want to comment on contemporary society, its people and events, but I don’t want to speak for others.

Sociology becomes important for me to have the courage to engage with stories talking about the world. It encourages the complexity within the story, and it helps me understand what I see and what I am part of.

However, I find that academia on its own can be rather limiting since it has a very restricted audience. Photography opens up sociological topics to a much broader audience and as the nature of the medium of photography allows for an interesting tension between ‘truth’ and ‘fiction’, I feel much more comfortable communicating in pictures since I don’t want to try to tell truths or pin down people or events to numbers or theories. I want to engage with the ‘real’ world in a more personal and creative way. The ‘sociological’ part of my work is focused on the way I go about engaging with a topic as well as with my subjects, I am not interested in the “scientific”, “knowledge production” aspect of it.

What’s the consequence of viewing photography within a sociological framework? How does it change how you shoot?

I am not sure how it changes since I have always worked this way, but I tend to view my photographic practice as project based. Often one project will influence the next one so there is also a general core interest that ties most of my work together. Since I am very interested in western attitudes that have to do with issues related to the limitations of the body (in relation to identity and how our bodies impact the way we see ourselves), I tend to pursue projects that are somehow related to this phenomenon. The idea of a ‘failing’ body is something that we in the west don’t seem to be able to accept. Disease, aging, and dying thus represent big taboos and a big part of our lives are centered on this battle in its multiple forms.

I always begin a project because I want to learn more about the subject matter and there is always more to a project for me than just the image making. I often work on long term projects which means developing relationships and maintaining an exchange with my subjects over time. Also, I tend to work on projects where access needs to be “gained” in one way or another – to a specific site, or through a specific relationship. I find photography in itself to be a rather aggressive act so when I engage with other peoples stories I appreciate sociology’s rigid ethical framework, something I often find is missing within the photography world.

Into Oblivion is a devastating set of photographs. You mentioned you spent months reading literature on Alzheimer’s before starting the project. What was your first step in pre-production, exactly? Which ideas about aging did you want to explore?

The whole project came about by chance. I was part of a small collective of recently graduated photographers in Paris and our old school transferred a message from the hospital. The very dynamic director of the hospital in question had made a call out to various art schools because she wanted someone to come and photograph. We decided to give it a go and eventually ended up getting involved. Heavy administration and long delays made most the members of the collective abandon the project and eventually I was the only one left. I had a rare opportunity to gain access to photograph in a hospital, something I had always been interested in doing. I did not want to let that opportunity go. The wonderful director who initiated the contact was acutely aware that questions related to ageing and the institution get too little attention within society. She was willing to take a risk and get involved with me in order to perhaps stir the pot a bit and incite debate about these difficult topics.

As I embarked on the project, I had also just signed up to study Sociology so I started to read up on topics related to the project (sociology of care and the institution, care policies, spatial segregation of generations etc.) However, as I familiarized myself with politics and theory, this was never intended as a way to produce a pre-conceived idea of what I was to be confronted with and this had no impact as to what I was to learn, witness, or experience as I began to spend time at the hospital but I do believe that I would not have been able to fully understand nor accomplish the project without the sociological framework that I managed to obtain. To have the time to thoroughly read up on the subject matter was crucial for me and it opened my eyes to many of the difficulties I needed to face to properly understand and contextualize the situation photographically.

You’ve said that, “when taking on difficult subjects, a visually compelling image can lure you into taking a closer look”. I’m curious about your technique in a photograph like this one. Could you explain how you approached composition, color, and tone with it? How many shots did you take?

I am interested in developing a visual language that challenges more traditional practices of documentary and portrait photography. I want for my photographic work to provoke questions and I hope it can create an alternative view of what may have been forgotten, or just simply ignored in a world obsessed with beauty and youth.

For the Into Oblivion series I found myself in a situation that could easily have become “too hard” for a viewer to engage with because of the nature of things. In terms with how to deal with this visually, heavy shadows or added contrast would, in my opinion, have made this image less accessible. The composition is very simple and straightforward. Most of the pictures of the people in front of the door have their backs to me, I have photographed them as they are facing the door, but this image also included me since this particular lady was in conversation with me at the time so it seemed appropriate to have her look back at me through the camera. She kept packing her belongings and set out to leave the ward several times per day. She asked me to open the door, whilst also complaining about the fact that we were both locked in. I did not take many pictures, perhaps one or two. Often the situation would change quickly so there was no time for tripods or multiple shots.

When out shooting, did you run into a conflict between aesthetic choices and documentary intent? What guided your aesthetic choices? Any personal rules?

To me, it’s more about finding a way to visually convey something in an compelling way that also makes sense for the nature of the project. If that doesn’t happen, the project will most probably fail… I don’t want either for my aesthetic aspirations to suffer or for the message to be blurred, so it’s important to find the balance. Some nice looking images might be excluded if they don’t carry meaning and vice versa but that is just part of the process of editing. I work really slowly though and tend to digest and analyze what I do for extended periods. This is important for me in terms of figuring out what works and how to make progress.

The photographs of the door in the Into Oblivion series for example came together towards the end of the project. I would shoot an image of the door here and there, and then, once I had accumulated a few, I realized that the image carried significant meaning. It became a way to visually convey the sense of exclusion, not only on a personal level for the residents in the ward, but also on an institutional level, where the increased exclusion of elderly people in society can be felt in these pictures. I then started focusing more on the activity around the door and on shooting more of these images.

At times, you intervened and distracted some residents from wandering to the door. You’ve said that it was difficult to watch, yet your most powerful images are these. When did you know it was time to put the camera down and help? Did it all depend on the resident’s mood?

Yes, of course, it did. If a resident was distressed or upset, I would talk to them and try to reassure them. Throughout the project I spent a lot of time in the hospital and I grew very attached to the residents in the unit. I would keep in touch with certain family members whilst I was away, and it was painful to go through difficult times with them. The worst bit of Alzheimer’s disease is that the affected person will go through moments of lucidity where they realise that they are loosing their memory. This can cause behaviour difficulties such as aggressiveness, eating disorders, increased anxiety or depressive tendencies. It is also very common to have a strong urge to go ‘home’, often to an imaginary childhood home. This is where the constant wandering and the struggle with the door begin. That was very difficult to watch. However, they were also easily distracted, so if I was present in the unit, by chatting to a particular resident or doing something with them, I could sometimes prevent them from entering this state simply by being there. Of course it did not always work and residents would have ups and downs, but I would definitely not just stand and wait for these moments to appear.

I justified my presence by spending most of the time in the ward with the residents just like any volunteer. My presence became a welcomed kind of animation, I was there, available, and in no rush. By being there, I was able to attach the residents to the present and this felt very meaningful. If they were left to themselves, they would easily drift into an otherworldly state that could be distressing and upsetting. Although activities and outings took place as part of the daily routine within the ward, my main role became that of a human presence during the hours when the activities and the presence of staff were elsewhere. Spending time in the unit during the quieter hours allowed me to better understand the course of the day from the perspective of the residents. I also came to have an understanding of the stark contrast between the times when staff were present and the times when residents were alone.

Monette & Mady also deals with aging, though in a more surreal way. Could you explain how this project came about? How did you approach direction for the staged images?

The Mady and Monette project (a portrait of the life of identical twin sisters Mady and Monette) came about as a direct result of working on the Into Oblivion project. Until the year 2010, I lived in Paris and I used to see Mady and Monette on the streets in my neighbourhood. I was instantly fascinated by their identical outfits and synchronized corporal language. It took me several years before I approached them. Their presence was brewing in the back of my head while I was working on the project at the hospital. As I became increasingly aware of the questions and stereotypes that are related to aging, but also to how elders are portrayed in the media, Monette and Mady seemed completely indifferent to this in the playful way they carried themselves and stood out from the crowd. They didn’t seem to have an age.

This project highlights a positive and alternative attitude to aging, since Mady and Monette refuse to conform to the stereotypes that are related to aging. At the same time, the project is just as much a commentary on how disruptive and fascinating it is for us “singular people” (as Mady and Monette would say) to witness how one identity expands into two physical bodies. This makes us think about the limits of our own identity, our ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ and how we are constantly in conversation with ourselves.

Since I was interested to reflect Mady and Monettes own vision of themselves in the world and since performing (on the streets, on stage or in front of the camera) is such a big part of their life, I decided to mix my more documentary-style images with some more staged scenarios. The more posed photographs are alternated with pictures of the sisters interacting naturally as they go about their daily business. Since Mady and Monette are both eccentric yet very private people, this combination reflects their lives, particularly since it is not always obvious to tell the two approaches apart. This addition of fiction makes for a dreamy atmosphere, a bit like a mirage that reflects my initial impression of them. The streets of Paris make the perfect backdrop for such ambiguity to be played out, confusing us with its references to fashion, film and art. It makes the documenting of everyday events somewhat surreal.

What have been the greatest lessons photography has taught you about life? Any epiphanies while interacting with so many people?

Photography is for me a way to engage with and comment on the society I live in. It opens doors and allows for new encounters and experiences and I try to use it as a tool to try and understand my surroundings. When I take pictures I am just a person who is trying to make connections and interact with the world around me so I just try to do it in the best and most respectful way I can.

Be sure to check out all the work of Maja Daniels on her website!