Cinematic Portrait Photography with Emine Gozde Sevim

Emine Gozde Sevim is one of eleven photographers who were awarded this year’s Emergency Fund from Magnum. Given to projects that Magnum considers in need of critical attention and support, the grant helps experienced photographers continue work on documenting social issues. Sevim received the grant for her on-going project Homeland Delirium, a project that started in 2013 during the Gezi protests in Istanbul.

Sevim shoots in what she calls an impressionistic style — merging cinematic aesthetics with documentarian subjects. Her projects are as much about her thoughts and feelings as they are about the people and conflicts she’s photographing. I spoke to Sevim over email about Homeland Delirium and her first photobook, Embed in Egypt, that will be published this summer by Kehrer Verlag.

How did you get your start in photography? How would you describe your work?

My first photography course was in high school, within a special program of the school, which focused on large-format photography. Accordingly, the first pictures I made with some knowledge and consciously were made with a view camera. Today, my tools vary but my goal, no matter what camera I’m using, is to stay versatile in translating experience, letting the mood dictate, so to speak, the photographs I make.

Do you remember your first—very first—childhood memory? Do you think this memory and its emotional pull might have influenced your work?

I have a glimpse in my mind of what I think is my first childhood memory, which is when I cut my forehead while trying to reach/fly like the birds I saw at the window. I fell and cut my forehead, and I remember seeing the blood run down the front of my left eye. I can’t remember it hurting, but I remember my aunt and my mom seeming very worried about all that blood. Perhaps a psychoanalyst could really help me analyze the role of this memory for what I do today, but, on my own accord, I only learned, in literal terms, that I can’t fly.

Why do you think photography best suits your documentary pursuits?

Personally, I don’t believe these hard-line categories — documentary vs. fiction, photography vs. film, etc., — need to exist as mutually exclusive categories to choose from. Thus far, Cinematic portrait photography made in the documentary tradition has felt to be the best medium to translate the relationship I’ve had with the historical discourse that’s developing, but I didn’t decide on this preceding the experience. In fact, when I first arrived in Egypt, I was filming a lot more than making still photographs. Then, the experience changed: hence my relationship to the place and to what was happening around me did as well. Somehow, the stillness of photographs, portraying a slice of time left in the past, seemed more thorough about capturing the feeling of memory than moving images could do. That being said, I believe in having a camera with both still and movie functions. Why should I limit myself, or ascribe myself to titles (i.e., “photographer” or “filmmaker”)? The same goes with documentary vs. fiction, in that sometimes a fictional work can better communicate one’s feelings, experiences, etc. Of course, presenting fiction as documentary is never acceptable and ethical, so I’m not speaking about tricking the viewer. It is rather what keeps one up at night and finding the most organic tool to channel it, and, perhaps for me, one day it will be a script that I will be writing, a fictional movie that I will be making.

Did Homeland Delirium start alongside your return to Turkey? Do you think shooting in your own country changed the way you approached the project? If so, how?

On the way to regions farther east, I always made a point to stop in Istanbul to visit my family and spend time in the city where I was born. During these trips I always made photographs. However, “Homeland Delirium” resulted once a feeling, which dictates the aesthetic language of the work as well, took over, which coincided with the period after the Gezi Protests in 2013. I hope to remain true to the feeling of all experiences in the stories I will tell, which for me means, inevitably, my language will need to be dynamic — just as my experiences collectively continue to form my approach in storytelling.

You said that you aimed for an aesthetic inspired by cinema rather than everyday reality for this project. You called it an impressionistic approach. What does an impressionistic approach mean to you?

Recently, I began thinking about this in relationship to the role of history, the collective of narratives, and the times we are living in. We are all well acquainted with the fact that on one hand more people take pictures and look at pictures than ever before. On the other, photography has less impact than it did in a feature in LIFE Magazine in the 60s, for instance. Though some of them can be very important pictures to inform the world at an instance, personally, I have many questions about the role of media in shaping history and the language by which we’ve come to define it. I wasn’t actively seeking for a different approach; my main concern is to remain genuine. One of the best piece of advice I ever received was that there are no rules to abide by in finding one’s language. So my impressionistic (to be more exact: documentary impressionistic) approach comes from the relationship I have with my surroundings, finding the world I experience, the scenes manifested in everyday life that are so hard to believe, at times, that they feel like scenes from a movie.

I was wondering how were you able to achieve this aesthetic. For example, in this one, which photographic elements were necessary to conveying this feeling?

This process is a lot more subconscious for me than it can be put into words. At the very instance of making the photograph, there are numerous elements one can’t control. It is like a dance but one doesn’t know the routine. So no rules, no formula, which actually allows to be completely free, but one needs to give into the harmony of the scene.

What did this aesthetic allow you to do that a more conventional reportage style couldn’t? Did it give you more freedom to look at things you wouldn’t have otherwise considered?

However difficult it is financially and practically, working independently has allowed me to remain mentally free in what I photograph and how I photograph. This is also a very lonely and personal place to create work and except news photography, I am curious and interested in other ways of working to expand my horizons. Though for any photographer, working with other organizations, I hope, is not to dictate the language of the author but rather for a mutually beneficial collaboration.

The project’s still in progress. Where do you see it going forward? Has anything changed in Turkey because of these protests?

The protests of course affected the country and the people both for the better and the worse. To know that this collective consciousness among those who felt alienated for so long, to feel not so alone is very important. However, unfortunately, what begins with most innocent hopes and intentions, in the meantime, can lead to harsher conditions on the ground. I sense this in Turkey now, in that, tensions, especially with the region more in turmoil than it was back in 2013, are higher. It is hard to pinpoint where things will go because there are too many variables at stake. Accordingly, I’m trying to keep my senses open to all the possibilities so that “Homeland Delirium” captures this as a long-term project. This takes a lot of reading, watching, observing — a type listening with all senses — to then be translated visually.

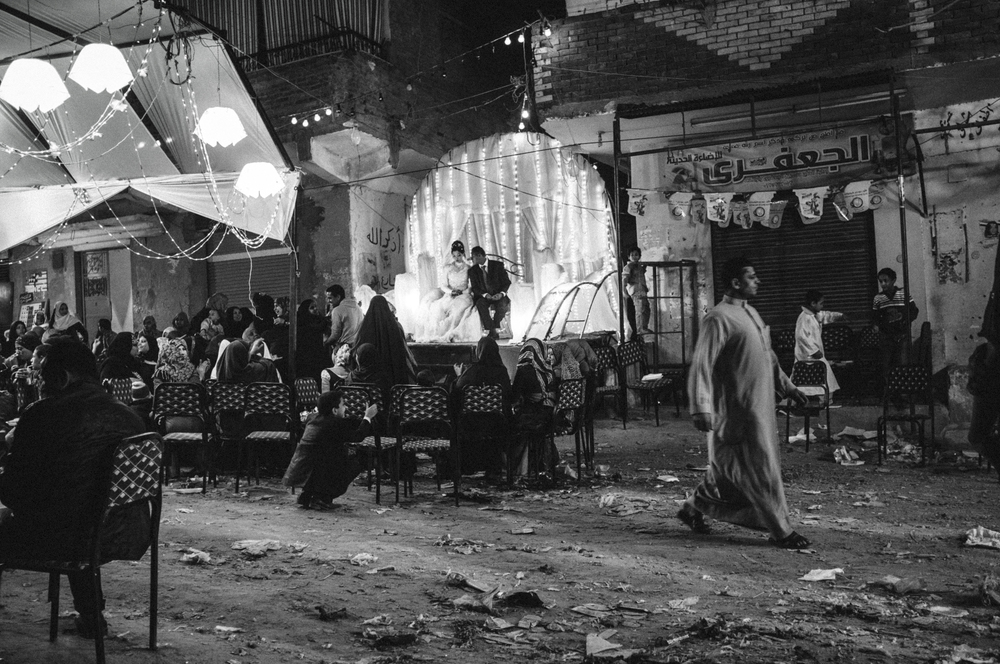

This is one of my favorites from Embed in Egypt. Could you explain how you were able to capture this moment?

Thank you! It was at a wedding I was invited to. We were seated a bit distant from the whole scene, which gave me a chance to see that overall frame. It was a wedding but with many components of life taking place simultaneously, the man going down the street (as the reception was in the streets of the neighborhood), the boy hiding behind the chair, the guests interacting among themselves, etc. it just felt what would have been the usual picture of a wedding with the alter, the bride and the groom in the center, was actually more complete this way and so I made this picture.

Has shooting this sort of photography affected your sense of beauty? Has it tarnished what you feel? Or made it more heightened? Something else entirely?

It is not the type of photography but to have the freedom to express oneself, I believe is a privilege and that of course makes me prone to sense beauty in everyday existence. Though at times, the experience can be very dire in the moment, I care too much to be part of that history to overlook the big picture. It is truly the journey that counts.

Emine Gozde Sevim (b. 1985 in Istanbul, Turkey) arrived in the United States in 2001 as a scholarship student in high school. She graduated from Bard College in 2008 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Photography, Sociology and International Relations. Her on-going body of work about the Middle East has been included in various exhibitions and publications internationally and has won numerous international awards and recognitions. Her first book project was shortlisted for the coveted MACK’s First Book Award in London (2014) and as a result was added to the National Media Museum Collection in Bradford, U.K. Sevim is also one of the 11 photographers who received a grant from the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund in 2015, in support of her most recent body of work from Turkey, “Homeland Delirium”. Sevim currently divides her time between New York and the Middle East. She is represented by East-Wing in Dubai.

You can see more of her work here.