We all have ideals. I had a friend, in high school, whose sole dream was to be a punk—or be nothing at all. I also had a friend who dreamed of being a writer—and nothing else. And there were a few who would have settled with no less than having one good poem to their name. Of course, I had friends who actually did do nothing. We all have ideals–what matters is when you lose them.

Art is inviolable. Art never falls for those who really don’t love it. Because we were too scared or too lazy or too comfortable, we started thinking about other things. That’s not bad. It’s growing up, I guess. Phillippe Diederich isn’t one of us, though, and that’s why I’m here writing about him. Phillippe Diederich is a writer and a photographer who stuck it out.

Born in exile, Diederich grew up in Mexico after his family was forced out of Haiti by Papa Doc Duvalier. Diederich found photography in grade school and was inspired by all the great Magnum photographers. Diederich has shot for the New York Times and has written a collection of essays, and recently the short story of Diederich, “The Falling,” won the Chris O’Malley Prize for Fiction from the Madison Review.

In this interview, Diederich talks about Mexico, his writing, and photography, explains how Diederich got his start, and reveals what’s like photographing revolutionaries in the heart of Mexico.

You’re a writer and a photographer. If there’s a better combination of pursuits, I haven’t found one. How did you get your start with photography? How would you describe your work?

When I was in the fourth grade, a friend of mine showed me the darkroom he had set up in his house with his father. He showed me a photo he had taken and developed. It was of an airplane in the sky. Very gray and full of dust. But I remember thinking, wow! Eventually, my father gave me an SLR and we set up a darkroom in the house, but it wasn’t until I was attending art school in Sarasota, Fl that one of my drawing teachers suggested I shift to photography. My father was a journalist. I originally told myself I was not going to go into photojournalism, because I didn’t want to live in his shadow. But really, it was what was calling me, and so I ended up a photojournalist. But my interest was not in typical newspaper work. I loved black and white photography and I admired the work of the Magnum photographers. That’s the direction I was trying to focus on.

You grew up in Mexico. You now consider yourself an exile. Bolaño thought all writers would eventually end up exiles – at least in their own imagination. Talking about writers in exile is not new. But how about a photographer in exile? How does being in exile affect your photography?

Well, my parents are Haitian, although my father is actually from New Zealand. They were kicked out of Haiti by the dictatorship of Papa Doc Duvalier. I was born in exile. I never yearned for Haiti because I didn’t know Haiti until I was in my early teens. So I grew up in Mexico without extended family, not as a Mexican, but slowly becoming one. The idea or concept of exile is something that is very complicated and layered. What is odd for me is that the place where I feel I’m from, the place I love, is Mexico. I am nostalgic for Mexico. I write about Mexico. I want to go back to Mexico. I almost feel like a Mexican exile. But I am not Mexican. How messed up is that? Photographically speaking, I don’t feel that my work is affected by exile because I always viewed photography as a vehicle to enter and discover new places. I viewed my camera and my vocation as a reason for being in strange lands—a license to wander. But when you look at someone like Joseph Koudelka whose work is inexorably tied to exile, you see his work also deals with wandering. Perhaps wandering is about being a photographer and vice versa. But one also has to wonder if photographers who do this kind of work might also be individuals searching for place.

Storytelling plays an important role in your work. Like individual frames of a film, your photographs point to a larger story yet are only narrative snapshots, glimpses of another world. I’m left wondering about the beginnings and ends of what you capture. This one is a great example. How did you capture this moment? Was your eye pulled by the multiple frames of action?

This image was taken during a train ride across Mexico’s Copper Canyon. I was working on a story about the ride, which is quite impressive. I walked up and down the train searching for moments that would capture what the train trip was like for the people. We had come to a station and I found the moment. The sleeping child caught my eyes, his boots. And the rest of the car was empty. But I was attracted to the various moments happening in different parts of the frame, the abstraction of the reflections. What I enjoy about this type of image is that it is like a short story collection, there are multiple stories going on in the same moment. And isn’t that how life is?

You have a great eye for honest expressions, those flashes of emotion that are usually covered up with polite restraint. Is it a conscious effort? Or is finding expression something you notice only later in editing?

It’s difficult to say. In all honesty, when I look through the viewfinder my focus is on the moment when things seem to come together, but nothing ever freezes, so it continues. As most photographers know, you usually don’t take one image of a moment. So it’s not this one picture, it’s really a series of pictures. If I spend time working on a story, working with the same subjects, I feel more relaxed and I can focus on the more delicate or subtle moments. Then, of course, it’s about making the right choices while editing.

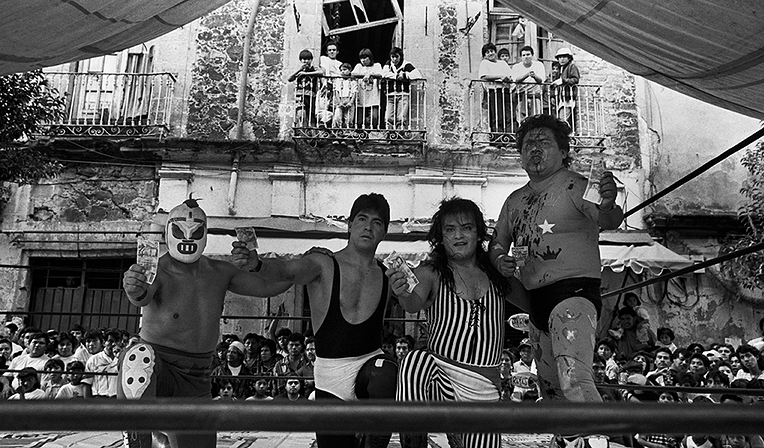

For example, in this one, the luchadores give you a priceless, authentic moment. Did you say anything to them? How did you get their attention?

These guys had just finished their show. They knew I was there taking photos. I’d been there all day photographing. When they finished, they got paid, they chose to turn to me and hold out their cash. They were so proud. It was very spontaneous on their part.

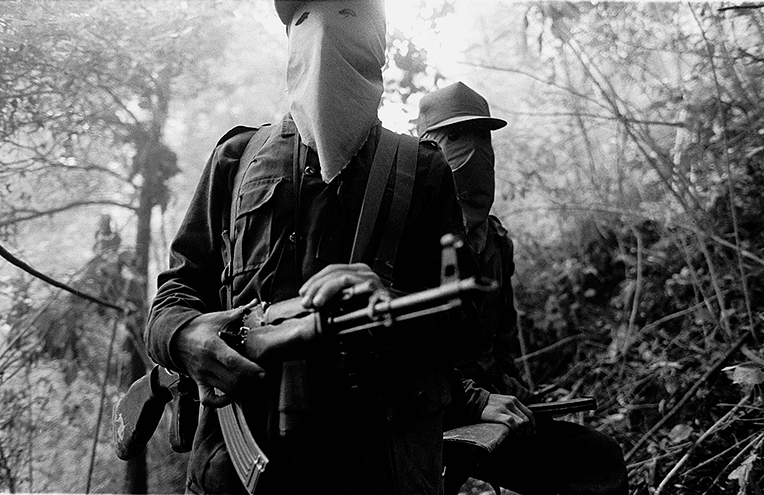

This is one of my favorites. Could you explain how this image was made from start to finish? What’s the story behind it?

In the middle of the 1990’s after the Zapatistas rose up in Chiapas, we had another group of rebels that appeared on the scene, the EPR or Ejercito Popular Revolucionario. They were well armed and very secretive. They had a few skirmishes in Oaxaca and Guerrero states which was their territory, the same place where the disappearance of 43 students happened this September. I had gone to meet the EPR with a few other journalists at different times. This picture was made somewhere in the mountains of Oaxaca. About half a dozen journalists had been invited to a press conference. The New York Times sent me to cover the conference. When we finally arrived at the site, after a long truck ride and hours walking up the mountains we arrived at the place high up in the mountains. It was misty, wet, cold and dark. And it wasn’t even a clearing in the side of the mountain. It was just a place where we stopped. The EPR command came and had their conference. I couldn’t really move from my spot. The mountain was steep. I didn’t have a very good angle of what was going on in front of me, so I turned and looked behind me and noticed these two guys at my back. I took a few frames and turned back to the conference.

I wonder if writing and understanding story have helped your photography. How much does writing influence your photography? Have you ever found coincidences between what you write and what you shoot?

I was a more active photographer before. Now I am a more active writer. Writing and photography work well together for me when an essay or long form journalistic story accompanies my pictures. This is the case in my book or magazine package “Communism and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” about Harley Davidson bikers in Havana. Both the essay and the images have worked independently: the essay in an anthology, and the pictures in a series of exhibits. But they have also worked together in magazines. It’s interesting. But with fiction it’s very different. I really don’t see my fiction influencing my photography or the other way around.

Has lessons learned honing your skills at either helped you in both? For instance, has editing for a reader’s attention helped you understand a frame’s negative space?

Because I was a photographer first, I believe photography has helped me tremendously as a writer. I see places and people that I have photographed popping up in my fiction. But see, it was photography that took me to places and introduced me to those people in the first place. Photography in many ways was the engine that propelled me to experience things, which have now found a way into my fiction. When I write about a place, when I describe setting, I am seeing the setting, and this is very cinematic or photographic for me. Editing photographs has also helped me understand how to edit my fiction: to have only what is essential appear in the image or in the story. It really does work both ways.

Who are the writers that have influenced your photography? Would you consider Roberto Bolaño an influence? And if no writer has influenced you, who or what has?

That’s a loaded question. I can’t think of a writer who has influenced my photography—not specifically that I can point out and define. I would say that Hemingway influenced my romantic notion of traveling and witnessing history, of having the right to wander—as I mentioned earlier, this idea that with a camera I have a reason to be. I love Bolaño’s work, but he’s not an influence on my photography. Especially since I didn’t read him until recently. When I was getting into photography back in the 80s, I was heavily influenced by the work of Magnum photographers like Alex Webb and Eugene Richards. But when Sebastiao Salgado’s magnificent book “The Other Americas” came out, it became my bible. Talk about writers influencing photographers. Salgado’s magical realism-like images in that book about peasants in Latin America turned my world upside down. It was certainly one of my strongest influences in photography.

Check out all the work of Diederich here!