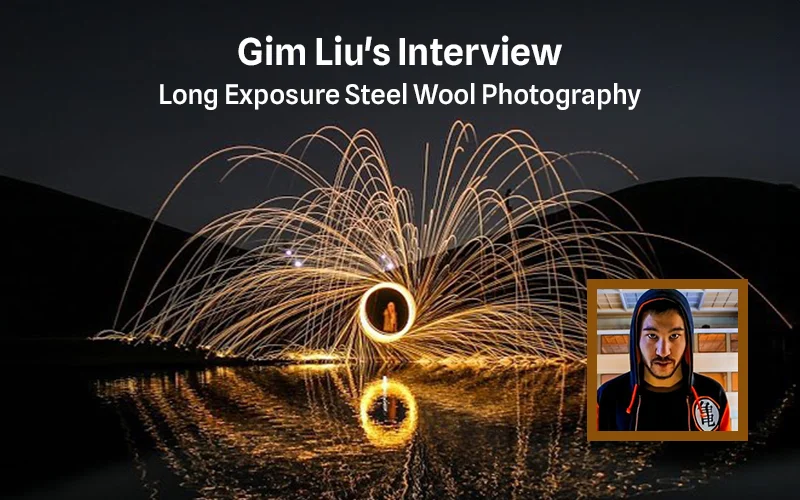

Some notes before the interview. This conversation took place via email between an office and an apartment in Los Angeles. I wrote the questions toward the end of the night of September 23rd. Near morning. But early or late enough to be considered neither morning nor night. Either way, I wrote them, proofread that, then went to bed.

I have the impression that this conversation could have taken place in the corner of a dark bar. Either there or a church that nobody attends. In fact, this church must have already been forgotten. Graeme Mitchell says he spent a morning on his answers. Mitchell has worked with W magazine, the New York Times, and New York Magazine, among many others.

In this interview, Mitchell talks about how he transitioned into professional portrait photography, explains some ideas behind his work, and engages in a conversation like an old friend would.

The answers and their questions have been edited and reformatted to aid readability.

You studied literature in college.

Yes, I studied literature and didn’t come to the visual arts until later. Literature informs me a great deal in both its form (books, namely), how it functions (a populous/democratic medium), and most of all in that it was my first love and my introduction to the arts.

So I have to ask: would you consider your work post-modern? There’s an understated complexity in your work.

As far as post-modernism: I think that postmodernism, deconstructionism, post-structuralism, etc., are frameworks we all think within now.

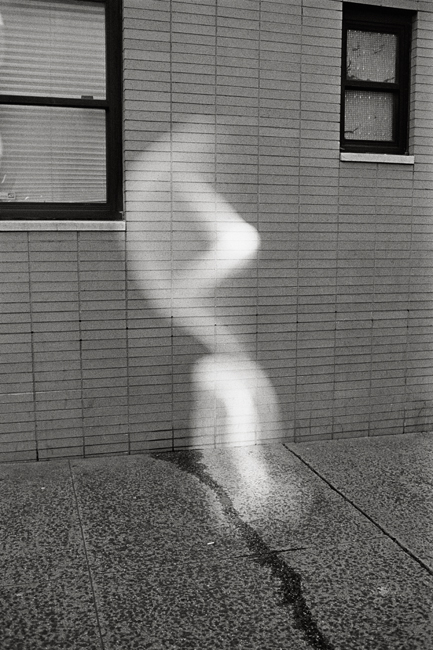

I can’t help imagining that you approach photography like a writer approaches their own writing. You work toward elegance by eliminating. For example, at first glance, Occurrences #9 seems simple enough (above), but if you stop and stare at it, it could be read in three ways. The first reading is immediate. It’s about what’s seen. You could say this image is nothing but a reflection, a found play of light. And that’s all. Something inside you wanted this reflection to be seen. Yet someone could say: What’s the point? The second reading would answer this question. These readers would say: The point is the light. They would admire the object as it is. They would appreciate the geometry of the angles, and how, if you look closely, the object resembles a person, perhaps a stick figure. The last reading – and this is why I consider your work post-modern, or modern, or at least responsive to the history of photography – requires imagination. It requires the reader to step outside the image and question you. These readers would wonder: what if an assistant angled a mirror behind you so you could capture the photograph? Whether you did that or not, the image still holds the same meaning. But the last reading circles back to the first. The immediate question becomes the only question: What is the point? But, again, that question leads to the second reading’s answer. But if there’s a fourth reading, what would that reading be? If the second reading answered the first, how does the fourth reading answer the third? What do you think?

Your reading of that photograph from Occurrences is example of what I mentioned earlier. So, yes, I’m a post-modernist, or the child of one, as we are all by now. Whether my work adheres to a postmodernist aesthetic (there isn’t one) is up to others to decide. We’re talking about a method of thinking, or rather talking about thinking, that is, what, 50 years old by now? When I watch a fourteen-year old work their phone, their camera, and the internet, I see how much more laterally fluid our system of thinking and discourse is now compared to when I was fourteen, when the internet was first coming into homes. Take what Conceptualism and, say, the Picture Generation, did over the last thirty years as art, and you’ll see that it’s now entirely natural and innate in how this fourteen-year old functions. (Unfortunately, it’s almost entirely within a commercially-realized market system now.) I can’t believe Richard Prince causes a stir when appropriating internet content. It seems by now redundant. To quote Allan Sekula, we now fully live to, “traffic in photographs.”

Anyway, that is only about postmodernism in the sense of it being an umbrella term, and about how these structures and terminologies of academia have become nearly too slow. The world now, its market systems and our use of information, moves too fast for them. The market turned out to be the ultimate appropriator. Usurping anything and everything (most powerfully those things in opposition) in a cycle to protect and sustain itself. So we’re not interested in serious ideas. There’s no time for them. There are too many practicalities at stake at any given moment. I make work to solve a problem or to work through a question. Theory is generally not a part of it until someone, you in this case, says it is. A post-internet or post-digital question, especially with regards to photography, is now a more relevant question, I think. How does a flat representation of the world stand up as important when it is ubiquitous? We live in a flat world (again after all these centuries!) through monitors and screens. How does taking more pictures benefit us?

People argue culture, and I don’t debate that, but I speak of the idea, or what’s at stake beyond the photograph. Make a picture into a sculpture à la MFA programs and there’s something there, too, I find interest in. Or not overthinking it and making stuff that looks good and getting paid is something, too. If you go day in and day out, there are bridges that must be crossed in your mind. Another Sekula quote I’ve written in a notebook beside me here is, I think, loosely relevant:

Just as money is the universal gauge of exchange value, uniting all the goods in a single system of transactions, so photographs are imagined to reduce all sights to relations of formal equivalence. Here, I think, lies one major aspect of the origins of the pervasive formalism that haunts the visual arts of the bourgeois epoch. Formalism collects all the world’s images in a single esthetic emporium, torn from all the contingencies of origin, meaning and use.

That’ll inspire the instagram feed! But, as much as I regard Marxist and Dialectical Materialism ideas as informative to my outlook on life, I also find it can lead to a cul-de-sac, as indeed any single strain of thought can. This leads me to that picture in Occurrences, which I consider beyond theory or representation. It simply was a moment of connection of being with time and light. It’s not representative of a subject or any idea beyond that which you might imagine. For me, it was simply an occurrence that I had the pleasure of being privy to and wanted to use to make the book work. And with it, I think fitting and also as balance to the Sekula quote, is a word from Jean-Francois Lyotard:

What art has at stake […] is something that is extraordinarily serious [and leads to] a primary interest in the most fundamental question of all: ‘why does something happen rather than nothing?’

Were you ever unsure of yourself? Does photography come easily to you?

Unsure, yes, all of the time! Insecurity within the process of making work is important to me. When I take a portrait for a magazine, I’m sure of myself. When I try to make work that’s important (to me as art) on the other hand, I’m stepping beyond what I know. Photography doesn’t come easily to me until it does, but at that point it’s less coming to me than it’s going through me.

What’s the depth of your planning? Part of me wants to believe you control everything that enters your frame. For example, in Andre Walker and Louise Parker (above), I wouldn’t be surprised if you had directed Mr. Walker to extend his left leg into the light. He’s a designer after all. Why not have the light sculpt itself around the bends of fabric? Or not, I don’t know. Was it a conscious decision to pose him in that way (even Ms. Parker’s hand seems intentionally ambivalent)? How do you usually approach direction?

It depends. Generally, it’s a balance of control and at the same time being open to what is good in a moment. It’s about seeing possibility, and then going for it and standing by what you see while also having the courage to let go and learn something new through it. I did put Andre’s pant legs in the light intentionally. We had talked about them, and he really loved that tailoring element on the cuff, so it was only natural. People overrate this sort of intentionality, though, and mistake it for seriousness or some sort of intelligence. It’s not a matter of that at all. It’s just a matter of personality and getting things done for any given artist.

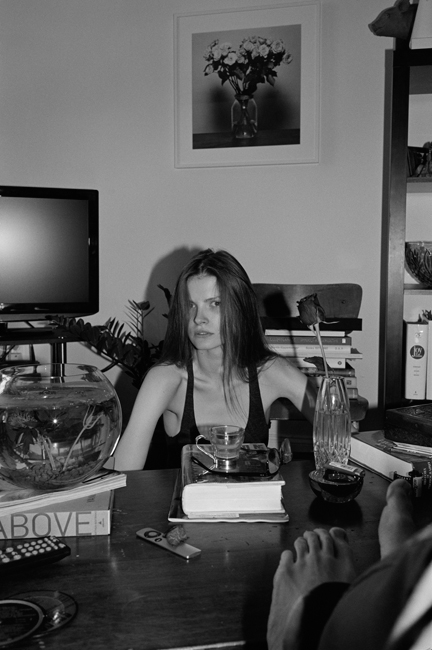

Speaking of Ms. Parker, my favorite photograph of yours is of her. Louise Looking at Herself is fantastic (above). If we were drinking together, I’d tell you that it’s a masterpiece. Could you explain how this image was made from start to finish? How did you explain the project to Ms. Parker?

Thanks. It is a good photograph to me, too. I met Louise, who is a fine photographer in her own right, for that picture I did of her and Andre for W magazine. I liked how iconically American her look was, and how troubling her beauty was, so she came over and I had her stare at herself in a mirror and discuss what it was to be beautiful, and I had her take that conversation on for a long time, deeper and deeper, probably more like fifty minutes or one hour. I just thought 35min felt more arbitrary and right for the title, hence that untruth.Then, I had her do the video piece eating cereal to sort of hark back to the cereal commercials of my 80s youth. That ideal beauty eating a bowl of cheerios! In addition, I’d also just started using this digital camera, so it was also a chance to see how it worked and to learn how to use the video part.

Back to Andre Walker and Louise Parker — why did you decide on color? What forces your decision between color and b&w? Is it a matter of story, or feeling?

It is a matter of economy and what seems like it will look best. I shot black and white almost entirely for ten years because I was broke, and it was cheap (I’d built a small darkroom so processing and proofing film was like a dollar a roll in costs), and then because I fell in love with the beauty of black-and-white prints. Now, I’m shooting more and more color, because I have a digital camera, and because it suits where my work is headed.

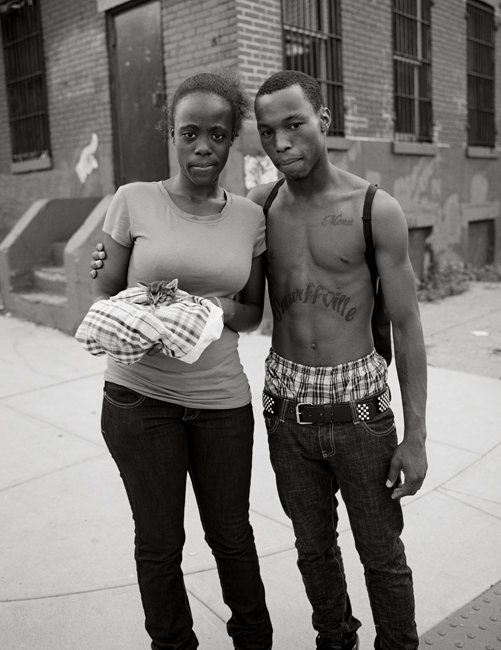

Couple w/ Kitten is difficult. I feel a lot of pain coming from the image. How did you find this moment? What’s the story behind it?

If I see people who interest me, I generally try to build up my nerve to ask if I can take their picture. More and more, I try to get them to come back to my studio, but, in my early years in NYC, I slept and worked in tiny rooms and spent my days on the street. This just happened to be a picture from that time, which to me stands up as still being interesting to share on my website.

Emily and Meredith are two art students you met in 2012. From that meeting, you decided to take their portraits. What drew you to them? What about them did you want to show the world?

Same story as above. I met Emily in the grocery store, and she was very beautiful (sometimes it’s as simple as that), and I asked her to come sit for a portrait. She then said I should meet her friend Meredith. I was mostly finding people to sit for me so I could work through technical matters for portraits and to add to my portrait portfolio so I could get more magazine work. For many years, I was largely focused on those things, figuring out how to take a picture I could get hired for, for the pragmatic reason of making a living – a reason that can’t be underestimated. Over the last year or two, I’ve transitioned more to focusing on art, but I’m proud of my background as a commercial-editorial photographer.

Conversation seems important to you. Do you have any questions for me? I’ll answer them then put them here at the end. Or if that’s too silly, who are your greatest influences? Any last words?

I love conversation! But no, no questions for now. Time’s up really. I’ve lost too much of the morning falling in love with my own voice, lol. Thanks for asking, though. Oh, influences: Influence is everywhere. A random thing you find on the street can be as beautiful as anything. It’s about seeing it, contextualizing it, and making it into something that engages people to think. As far as artists that influence me, that’s too long of a list.

See more of Graeme’s professional portrait photography work on his website!